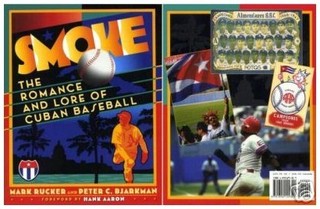

SMOKE — The Romance and Lore of Cuban Baseball (with Mark Rucker, Photo Editor)

Finalist for 1999 CASEY SPITBALL MAGAZINE AWARD and 2000 SABR HENRY AND DOROTHY SEYMOUR MEDAL

(AWARDS TO HONOR BEST 1999 BASEBALL BOOK)

“Smoke is visual, visceral energy ... rarely does a baseball book offer so much new information to a new audience (American fans) in such superb fashion.” — Sports Collectors Digest (January 2000)

PAGE CURRENTLY UNDER REVISION

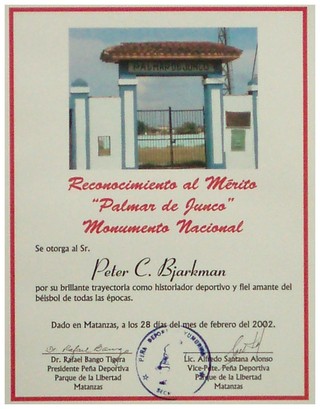

Recipient of special "Palmar del Junco National Monument" Award from Matanzas Sports Club

Award winning pictorial history of Cuban baseball produced by photographer Mark Rucker and author/historian Peter Bjarkman, covering the full range of nineteenth and twentieth-century Cuban baseball in spectacular coffee table volume format. A visual treat and one of the most strinking pictorial baseball books ever produced. Shrouded in mystery for decades, Cuban baseball has become the final frontier for fans of the sport in North America. An unprecedented collection of photographs, statistics, and lore, Smoke explores the depth and range of the island's baseball heritage—from its origins in the 1860s, to Babe Ruth and Ty Cobb's barnstorming tours, to Fidel Castro and the Cold War that closed off access, to Orlando "El Duque" Hernández of the world champion 1998 Yankees. The combined efforts of Latin baseball's leading historian Bjarkman) and the recognized authority on baseball images (Rucker) provide an exciting reading and viewing experience, bringing to life a rich baseball culture that has heretofore remained largely hidden from our view.

Reviewers' praise for Smoke — The Romance and Lore of Cuban Baseball

"However valuable the text, this volume is also a visual treat, one of those rare publications that belong on both the bookshelf and the coffee table."—Joseph L. Arbena, Harold Seymour website (www.haroldseymour.com)

"... SMOKE is visual, visceral energy ... Rarely does a baseball book offer so much new information to a new audience (American fans) in such superb fashion."—Sports Collectors Digest (January 21, 2000)

"Bjarkman's chronicle is a fan-friendly Cliff Notes version—brightly written and breezy but still managing to hit all the high points."—Kevin Baxter, The Los Angeles Times (September 23, 1999)

"In contrast, Peter Bjarkman's lively Smoke: The Romance and Lore of Cuban Baseball takes us back 125 years to the origins of the sport on the island. Though the book ... tills much of the same ground plowed months earlier by Roberto Gonzalez Echevarria's authoritative The Pride of Havana: A History of Cuban Baseball, Bjarkman's writing is far more accessible—and enjoyable—than Gonzalez's dense, academic style."—Baseball America (April 17-30, 2000)

Past-Era Cuban Baseball Legends

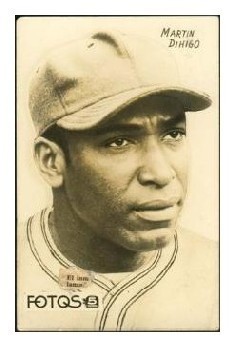

Martín “El Inmortal” Dihigo (DEE-GO) was certainly no latter-day case of admission into the Hall of Immortals (he was enshrined in 1977) driven by a guilt-ridden sympathy vote. Many rare distinctions marked Dihigo’s résumé alone and thus justified immediate Cooperstown enshrinement. Dihigo would, for one thing, eventually claim distinction as the only ballplayer elected to halls of fame in three separate nations—Cuba and Mexico would also eventually enshrine him. Here was also a ballplayer soon to be chosen (in an early 1980s poll) by surviving Negro leaguers as the all-time best black second baseman, while remarkably also receiving numerous votes as the best-ever performer at both third base and the outfield. And if these unparalleled achievements in North American Negro league venues and on island barnstorming tours were not hefty credentials enough, Dihigo has also once been an incomparable Mexican League legend, hurling that country’s first-ever pro-league no-hitter (1937) while surprisingly also pacing the Mexican League circuit in batting percentage during the following summer season. In Cuba in the years before communism and the rise of amateur sport Martín Dihigo was everywhere acknowledged as Babe Ruth, Joe DiMaggio and Walter Johnson all wrapped up in one muscular dark-skinned package. Unfortunately it was that dark skin which also made him Cuba's greatest loss for several generations of North American baseball watchers.

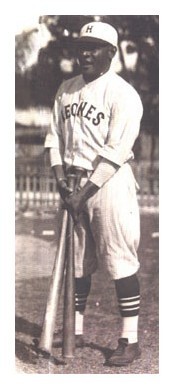

Cristóbal Torriente emerged from the early century Cuban winter league scene as an unparalleled slugger and defensive wizard the Pittsburgh Courier (which tabbed him among their all-time black all-stars in 1952) once labeled “a prodigious hitter, a rifle-arm thrower, and a tower of strength on defense” (as quoted by John Holway). In a period which saw the rise of numerous island nonpareils—a large percentage of them black and thus unavailable to the U.S. majors—one alone seemed without peer when it comes to judging overall Negro league careers both North and South of the Florida Straits. Of all the players produced on the island during the teens and early twenties, perhaps only Méndez can rival the diverse talents displayed by Torriente. “The Cuban Strongboy” was almost as renowned for his flawless outfield play as for his heroic feats with the bat. But it was his hitting that in the end set this light-skinned but kinky-haired paragon apart from the pack. Torriente was arguable the greatest Cuban-born of the pre-revolution era with his .350 winter league average and almost-.340 summer season mark up north. Torriente’s feats in Chicago with Rube Foster’s American Giants have been catalogued and praised by Holway, Riley and a host of other blackball historians. His achievements back in Cuba were just as noteworthy if not more so. He would eventually claim two Cuban League batting titles playing for Almendares to go along with the less-well-documented crown he earned as a Negro league barnstormer. Oversized and sometimes fenceless Cuban league ballparks of the era may have converted many of Torriente's towering blasts into long doubles and triples or even longer outs, but there are certainly existing stories enough remaining about some of his prodigious pokes into distant grandstands to keep the legend alive and smoldering.

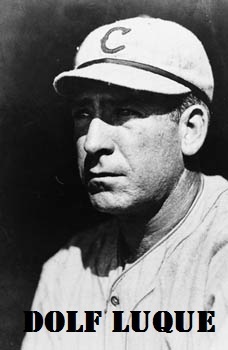

Adolfo “Dolf” Luque (LOO-KAY) holds a rare place in Cuban baseball lore—the only Caribbean islander to earn even a modicum of big league fame during the first half-century of modern major league history. Between Nap Lajoie and Jackie Robinson, Cuban big leaguers were restricted (largely by the odious “color line” imposed by North American club owners) to brief “cup-of-coffee” curiosities like Rafael Almeida, Armando Marsans, “Mike” González and a host of similar near-shadows. Luque, by sharp contrast, was something altogether special even if never fully appreciated in a sport still highly prejudiced against intruding “foreigners.” His big league credentials would at the end of two full decades (1914-1935) of service nearly approximate the numbers posted by many of his contemporaries destined for Cooperstown, including 194 victories, a franchise single-season victory total in Cincinnati in 1923 (27 wins, 1.93 ERA), and two league ERA crowns (1923 and 1925). Luque’s legacy includes the following boasting points: the first Latino to pitch in a World Series and win a World Series game; the first Latino hurler to post 100 big league wins; the first Latin American hurler to pace either major league in victories, ERA, the first Latino to pitch and win both ends of a big league doubleheader (July 17, 1923). Outside of the majors Luque was the only manager in the pre-revolution Cuban winter league to direct all of the "big four" Cuban ball clubs (Almendares, Cienfuegos, Marianao and Habana); he also trails only Miguel Angel González in years of island pro-league service or managerial success (total victories and pennants won).

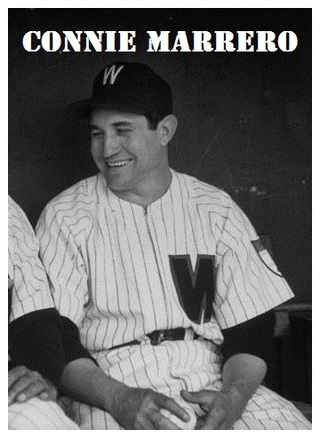

Conrado “Connie” Marrero remains one of the island’s greatest pitching heroes, even if his brief big-leagues sojourn with the Washington Senators (1949-1953, while already in his early forties) was anything but eye-popping (39-40 overall won-lost record, 3.67 ERA). His stature on Cuban home soil rests squarely on his brilliant amateur career in the early and mid-1940s, topped by a memorable confrontation with Venezuelan ace Daniel “Chino” Canónico that decided the 1941 Amateur World Championship series in Havana. Marrero also wrote a lasting legacy in the late 1940’s with the Havana Cubans of the Class B Florida International League; the then-35-plus junkballer posted successive 25-6 (1947), 20-11 (1948), and 25-8 (1949) campaigns while also striking out 586 while walking only 117 batters. Felipe Alou remembers Marrero as owning a windup that “looked like a cross between a windmill gone berserk and a mallard duck trying to fly backwards.” Señor Marrero—dubbed “the hick from Laberinto” back home in Cuba—thus always seened (away from his native soil) something more of a sports world cartoon than a true big-league baseball icon. But that fact that he was already a substantial legend on native soil before striking down a single American League batter is a most significant footnote to the entire Marrero saga.

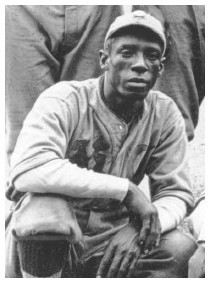

José de la Caridad Méndez—universally known to baseball historians as “El Diamante Negro” (“The Black Diamond”)—like Dihigo—was fated to remain outside the “white only” North American major leagues, though he has now finally found his place in professional baseball’s Valhalla at Cooperstown. Of the earliest Cuban baseball legends built upon the foundations of encounters with touring U.S. big leaguers, none was larger than that of the fast-balling Méndez. Over the course of four autumn sessions (1908-1911) the skinny kid from Matanzas faced five big league clubs in 18 games and won a total of 18 decisions, while dropping seven and tying one. On November 5, 1911 he blanked the Philadelphia Phillies; in 1913 he also no-hit the Birmingham Southern Association club for good measure. The startling performance perhaps was a string of 45 scoreless innings that included 25 against major league lineups. But there were also other remarkable moments that nearly topped the astonishing shutout streak, and none sticks out more than a Méndez debut against Cincinnati on November 15, 1908, when he tossed a sterling one-hitter, won 1-0, and lost his “perfect game” with two outs in the ninth on a scratch single by future Yankees manager Miller Huggins.

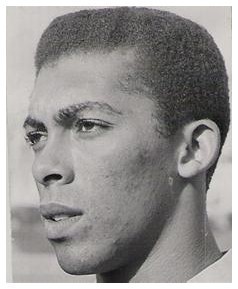

José Antonio Huelga (Sancti Spíritus) might well have been Cuba’s greatest pitching genius ever, including any of the stellar big leaguers (Pascual, Ramos, Cuéllar, Orlando Hernández, even Luque) or blackball professionals (Méndez, Bragaña, Cocaina García) from lost decades before the society-altering 1959 revolution. Some content that this slender righty was indeed the best ever seen on the island, especially given the brevity of his brilliant career. But the script fate had in store for Huelga—his life was snuffed out in a tragic July 4, 1974 automobile accident after only seven stellar Cuban League seasons that included the lost career ERA (1.50) on record—would only in the end make him Cuba’s most tragic post-revolution baseball story. Huelga will nonetheless live forever in Cuban baseball lore solely on the strenf\gth of his gutsy dual performances in two unforgettable playoff games with Team USA that decided the 1970 Amateur World Series showdown in Cartagena, Colombia. The first of these games was the celebrated duel with future big leaguer Burt Hooten (a 3-1, 11-inning victory) that most veteran Cuban baseball watchers to this day still judge the most artistic game ever played during top-level international competitions.